If you write reports, proposals, policies, or briefing notes, you already know the quiet pressure that comes with the word “Submit.”

Will the reviewer skim your document and grasp the point, or will they stall, confused, and push it down their inbox? In fast-moving business and government environments, that gap often decides whether your work is approved, funded, or quietly set aside.

Key Takeaways

- Clarity issues are easiest to spot when you read with your reader in mind, not with the draft still in your head.

- Confusing structure, vague wording, and unexplained assumptions are three of the most common clarity problems before submission.

- A slow, out‑loud read often reveals tangled sentences, missing links in logic, and tone shifts that silent reading misses.

- Getting distance from your draft, by taking a break or printing it out, helps you see where your meaning is muddy or incomplete.

- Targeted editing for clarity improves credibility with reviewers, clients, and readers, and reduces the risk of avoidable revisions.

In this article, I will focus on how to check for clarity in writing when time is short and stakes are high. I will share three practical ways to spot clarity problems early, so you can use strong writing that makes your work feel professional, easy to act on, and respectful of your reader’s attention. These methods work whether you drafted the document yourself or are revising an AI-assisted draft that still needs a human brain and eye.

Let’s start with why clarity matters so much in the first place.

Why Clarity Can Make or Break a Submission

In real life, clarity looks very simple: a busy reader can skim, the reader understands your main point fast, and know exactly what to do next.

When that happens, your document is easier to trust. Leaders are more likely to approve a recommendation when they can see the argument clarity. Funders are more likely to support a proposal when they understand the problem, the solution, and the payoff without re-reading. Policy audiences are more likely to accept a decision when the reasoning is clear and the outcomes are specific.

To get there consistently, I have a straightforward, repeatable process for how to check for clarity in writing before I send anything to leaders, clients, partners, or the public.

What “clear writing” really means in business and government

In this context, clear writing is neither flowery nor dramatic. Very plain writing is the best option. This clear writing has four basic qualities:

- One main message

- A logical flow of ideas

- Plain, direct language

- A clear ask or next step

Here is a quick example from a memo subject line:

- Unclear: “Update on ongoing initiatives”

- Clear: “Decision needed today on Q3 hiring freeze”

Or from a briefing note opening:

- Unclear: “This note provides background on several matters related to departmental priorities.”

- Clear: “This briefing note asks for your approval to pilot a remote service model for regional offices in 2026.”

Clear writing is not about “dumbing things down.” It is about respecting the reality that your reader is juggling dozens of priorities and has limited cognitive space for guessing what you mean.

Common clarity problems that slip past spellcheck

Spellcheck will catch “pubic” when you meant “public,” but it will not warn you when a deputy minister or board chair cannot find your main point.

The problems I see most often in business and government drafts are:

- The main point is buried on page three.

- The purpose of the document is vague or never stated.

- Key terms are abstract, so readers can interpret them in different ways; these ambiguities are examples of vague writing.

- Jargon and acronyms are used without explanation.

- Sections send mixed signals or present conflicting messages.

- The document ends without a direct ask, decision, or next step.

The three methods below are designed to help you catch exactly these issues before you submit.

Way 1: Use a Simple Reader Test to Check Your Core Message

The first check is quick and human. It lets you see your work the way a busy executive, director, or minister’s office would.

Think of it as the “busy reader test.” Even under serious deadline pressure, you can do it in five minutes and dramatically improve how clearly your purpose comes across. If you want a step-by-step version of this pass, try this quick Clarity Check.

Ask one key question: “Can a busy reader get my point in 30 seconds?”

Set a timer for 30 seconds. Then pretend you are your most impatient reader.

Look only at:

- The title or subject line

- The first sentence or short opening paragraph

- The main headings, if it is a longer document

Without reading the details, ask yourself three questions:

- What is this about?

- Why does it matter now?

- What do I want the reader to do?

If you can’t answer those three questions in plain language after a 30-second skim, you have a clarity problem at the core.

Sometimes the fix is small, such as practicing concise writing by sharpening a title, rewriting the first sentence, or adding a simple line such as “You are being asked to approve…” at the start. Other times, this test reveals that you are trying to do too many things at once, and the document needs to be split or refocused.

Check your purpose and audience in one short sentence

The second step is to make your purpose and audience visible to yourself. I use a short sentence frame:

“I am writing this to [decision-maker or group] so they can [action or decision].”

For example:

- “I am writing this to the Executive Committee so they can decide whether to renew the vendor contract for 2026.”

- “I am writing this to the Minister’s Office so they can approve public communication on the new housing incentive.”

- “I am writing this to regional managers so they can prepare staffing plans under the revised budget.”

If you struggle to complete that sentence in straightforward language, your document probably is not clear yet. Maybe you are not sure what you want from the reader. Maybe the audience is too broad, or you need help defining key terms for the decision-maker or action. Either way, it is safer to fix that now than to submit something that leaves them guessing.

You never need to include this sentence in the final document, but it should shape your choices: what you emphasize, what you cut, and what you ask for.

Highlight your main message and action in the opening

Once you know your purpose, bring it to the front.

For a memo:

- “This memo recommends approving a one-year extension of the pilot program while we collect additional data.”

For a briefing note:

- “You are being asked to endorse the proposed framework for community consultation on the transit expansion.”

For an email to a senior leader:

- “I am requesting your approval to proceed with the revised project timeline for Phase 2.”

Decision-makers should not have to search for your ask. If you hide it in the second page or in a dense paragraph of context, you are forcing them to work harder than they should.

When clients want deeper support with crafting clear, action-focused openings, that is usually the point where they reach for professional editing or coaching, rather than trying to fix it alone. I explain what that really means in this breakdown of what a ‘polish’ actually covers.

Way 2: Run a Quick Structure and Flow Check

Once the core message is clear, the next question is structural: does the document carry the reader through a simple, logical path?

Here, I shift from “What am I saying?” to “In what order am I saying it?” This is where I check clarity in writing at the document level, not just line by line.

Scan your headings to see if the story makes sense

For any report, proposal, or briefing longer than a page, the headings should tell a story all by themselves.

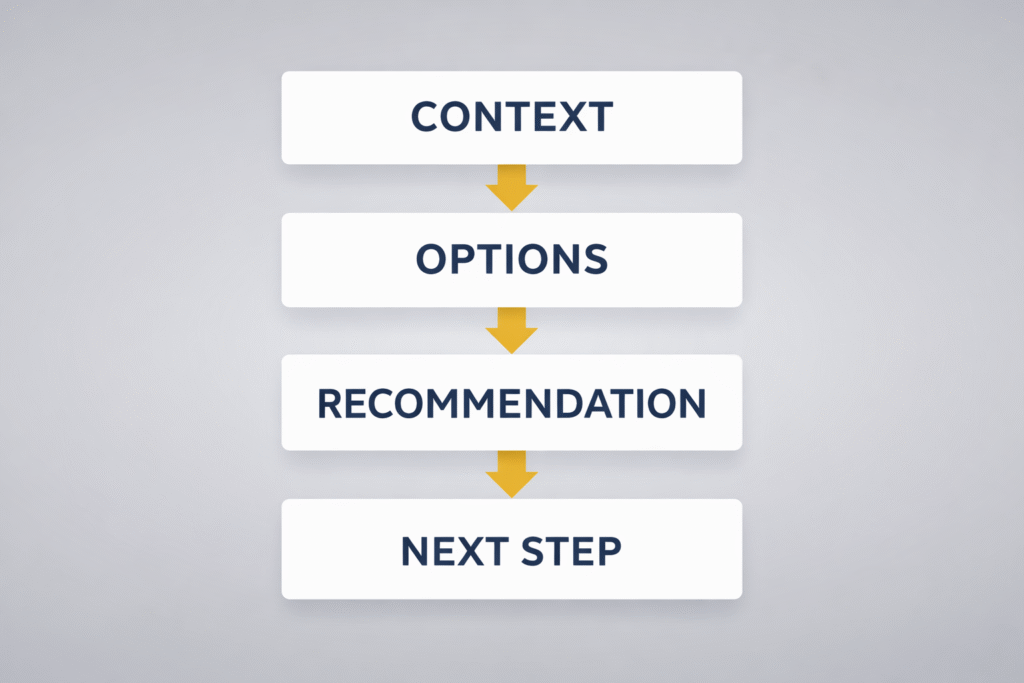

Try this: ignore the paragraphs and read only the headings and subheadings, in order. Ask yourself whether they trace a clear arc, such as:

- Problem or context

- Analysis or options

- Recommendation

- Next steps or decision

If you see vague or generic labels like “Background,” “Other considerations,” or “Miscellaneous,” notice how little they tell a time-poor reader.

Compare:

- Vague: “Risks”

- Clear: “Key risks for the 2025 budget”

- Vague: “Background”

- Clear: “How the 2022 service changes affected wait times”

Headings that state what the section actually delivers reduce friction. They also make it easier for a minister, director, or evaluator to navigate back to what they need later.

If you want to see how formal plain language guidance treats headings and organization, the checklists at PlainLanguage.gov are worth bookmarking.

Use one-question paragraphs for tighter focus

Inside each section, I like to think of every paragraph as an answer to a clear question.

For example:

- “What is the current problem?”

- “What evidence supports this option?”

- “What are the financial implications?”

If a paragraph tries to answer three questions at once, most readers will lose the thread. They may understand each sentence, but not how they fit together.

Here is a quick illustration of messy versus clear paragraph structure.

Messy paragraph:

“The program has generally been well received, and although there have been some complaints about delays, it should also be noted that staffing levels have fluctuated due to unplanned absences, which has in turn impacted processing times, so additional training and new technology may both be required if we want to ensure that the service standard of five days is met going forward.”

Cleaner approach, using the “one-question” idea:

“The program has generally been well received. Clients appreciate the new online application process. The main concern is delays. Processing times increased in 2024 because staffing levels fluctuated. If we want to restore the five-day service standard, we will need to add training and improve the technology platform.”

Each paragraph does not need to be one sentence, but it should have one main job.

Check transitions so readers never feel lost

Finally, I look at how sections connect to each other. Often, unclear writing is not about any single sentence. It is about the small gaps between ideas.

A simple check:

- Read the last sentence of one section.

- Then read the first sentence of the next section.

- Ask: does the movement feel natural?

If the jump feels abrupt, add a short transition phrase that shows the relationship. Helpful transitional devices include:

- “This means that…”

- “As a result…”

- “The next step is…”

- “In contrast…”

- “To support this recommendation…”

You do not need elaborate transitions everywhere. A few well-placed signposts can carry a senior reader smoothly from old to new information, from context to analysis to decision.

For more ideas, the PlainLanguage.gov checklist includes practical prompts about organization and flow that align well with government and corporate standards.

Way 3: Use Plain Language and Specific Detail to Fix Confusing Sentences

Once the big structure works, I zoom in to the sentence level. This is where you can quickly reduce misunderstandings, especially in policies, contracts, and public communication.

This is also where many AI-generated drafts sound polished but leave too much room for interpretation. A human review for plain language and specifics makes a real difference.

Swap vague buzzwords for concrete, specific words

Vague writing in professional language looks impressive at a glance but often hides the actual point. Common culprits include:

- “Optimize”

- “Drive engagement”

- “Leverage synergies”

- “Impactful initiatives”

Clearer versions use specific language to say what will actually happen. To avoid generalizations, opt for specific language that paints a clear picture.

Before:

“The initiative will leverage cross-departmental synergies to optimize service delivery.”

After:

“The initiative will combine three call centers into one team so customers have a single point of contact and shorter wait times.”

(Note how this uses strong verbs and action verbs to show the real steps.)

Before:

“This program will have a significant impact on stakeholder engagement.”

After:

“This program will require quarterly meetings with community partners and a public report on results every year.”

When you find a fuzzy verb or phrase, consider your word choice: “What would this look like in real life?” Then write that.

Explain or limit acronyms and jargon

Acronyms and internal jargon and big words are surprisingly expensive, in terms of clarity. They make new staff, partners, and members of the public feel like outsiders, and they increase the risk of misreading.

A simple rule:

- Spell out any acronym the first time you use it.

- Limit jargon that is not strictly necessary.

- Add a short explanation when a term might be new to part of your audience.

Before:

“The new KPI framework will be rolled out to all SMEs in the Q2 RAS cycle, in line with the updated OGPP directive.”

After:

“The new key performance indicator (KPI) framework will be rolled out to all small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the second-quarter risk assessment (RAS) cycle, under the updated Government Procurement and Planning (OGPP) directive.”

If your document is long, you can add a short glossary at the end. Even so, I would rather see key terms briefly explained in the body where they first appear, especially if you are writing for mixed audiences.

Read key sentences out loud to catch hidden confusion

One of the most reliable ways to catch unclear writing is to read important lines out loud.

Focus on:

- Recommendations

- Legal or policy language

- Public-facing statements

- Any sentence that has drawn confusion in the past

If you have to stop to breathe more than once, or if you trip over the words, the sentence is probably too long or too complex. Complex sentences often contain passive voice or unnecessary filler words, multiple negatives, problematic main clause interruption, unclear pronoun references, or heavy use of nominalizations.

Before:

“To ensure that we are able to adequately respond to emerging risks while maintaining continuity of operations across all regions, it is recommended that the Department authorize the development of a phased implementation plan that will, in consultation with key stakeholders, identify priority areas for investment over the next three fiscal years.”

After:

“I recommend that the Department authorize a phased implementation plan.

The plan will help us respond to emerging risks and still maintain operations across all regions.

Over the next three fiscal years, we will work with key stakeholders to identify priority areas for investment.”

To achieve this, fix the sentence structure by breaking it into shorter lines and switching from passive voice to active voice. This improves sentence structure further with parallel constructions, helps you reduce use of nominalizations, and lets you eliminate adverbs for more direct phrasing. The meaning is the same, but the path is easier to follow. Spoken clarity is a good signal of written clarity.

When a High-Stakes Document Needs Expert Clarity Support

There is a point where self-editing, even with good tools and habits, stops being efficient.

If I am working on a sensitive public communication, a large funding proposal, a complex multi-stakeholder report, or anything that could be quoted in the media or in Parliament, I take that as a sign to slow down.

At that stage, I might decide I want outside help to improve writing style:

- A professional editor who can see patterns and gaps I am too close to notice

- Someone who understands government or corporate decision-making and can test whether my argument will land

- A partner who can help me refine tone, structure, and plain language for style and clarity without flattening my voice or my organization’s style

The more I’ve revised a document, the more invisible my own assumptions become. An expert reader can step in where tools and checklists cannot, especially when clarity is directly tied to credibility and public trust.

Wondering how editors do that without overwriting your voice? I explain the difference, and what real voice-preserving editing looks like, in this quick breakdown.

Frequently Asked Questions About Spotting Clarity Problems Before Submitting

The most frequent clarity problems show up in three areas: structure, wording, and assumptions. Structural issues include sections in the wrong order, abrupt jumps between topics, and missing signposts that tell the reader where they are in the argument. Wording problems include long, crowded sentences, abstract nouns where concrete verbs would work better, and pronouns with unclear references. Assumption problems crop up when you skip steps in your reasoning, use terms your reader may not know, or rely on context that never actually appears on the page.

To check clarity for non‑experts, read with a simple test in mind: could a smart reader outside your field follow each step without stopping to puzzle out a term or leap in logic. Look for specialized jargon, unexplained acronyms, and references to internal processes that an outsider would not recognize. If you cannot explain a key point in one or two plain sentences, that section probably needs more context or a gentler ramp into the technical detail.

Reading out loud slows you down enough to hear how your sentences actually work, not how you intended them to work. You will notice where you run out of breath, where you naturally want to insert a pause that is not on the page, and where you stumble over tangled phrasing. Those are strong signals that a sentence is doing too much at once, that a transition is weak, or that your paragraph needs to be split so each idea has room to unfold.

One efficient pass is a “why and how” read. Move through your document and, for every key claim, check whether you have clearly answered why it matters and how it works. If a paragraph makes a point without showing its purpose for the reader, add a short framing line. If you state an outcome without explaining the steps that lead to it, add a brief explanation or example. This single pass often exposes missing links that confuse readers later.

It is worth calling in a professional editor when the stakes are high and the document has to work the first time, for example, journal submissions, book manuscripts, client proposals, or executive materials. If you have revised so much that you can no longer see what is on the page, an outside editor can assess structure, tone, and clarity with fresh eyes. A good editor will keep your voice intact while tightening language, repairing logic gaps, and preparing the document to meet the expectations of your specific audience or market.

Conclusion

Clarity is not an accident. It is the result of a few repeatable habits that you apply before you hit submit.

The three I have shared here are simple but powerful:

- Test your core message with a quick reader test so a busy person can grasp what it is about, why it matters, and what you want them to do.

- Check structure and flow so the headings, paragraphs, and transitions guide the reader through a clear story.

- Use plain language and specific detail to fix confusing sentences, especially where vague buzzwords, acronyms, and long sentences creep in.

Together, they give you a practical method for achieving clarity in writing every time you send something important into the world, whether you wrote it yourself or started from an AI-generated draft.

Clear writing is a skill, not a gift. The more you practice these checks, the more natural they become, and the more your work will carry the quiet authority of someone who respects their reader’s time. Careful human review, on your own or in partnership with a professional editor, catches grammatical errors and more than just issues with structure and flow, protecting your credibility and strengthening the impact of every submission you send.

For Government and Business Professionals Who Write Under Pressure

If you write reports, proposals, or briefing notes that need to land cleanly the first time, I can help you strengthen structure, clarify your message, and reduce the risk of confusion or rework.

I work with professionals in government, non-profits, and corporate environments who want editing support that improves clarity without flattening voice.

If you’d like editing that respects your voice and meets the demands of your audience, you can begin with an estimate. Together we’ll choose the level of editing that fits your needs. Ongoing or retainer support is also available if you prefer a steady partnership across projects.

For Managers, Leads, or Reviewers Overseeing High-Stakes Documents

If you’re responsible for a report, proposal, or policy draft that needs to be clear, credible, and ready for submission, I can support your team by reviewing the document for clarity, structure, and tone alignment.

You don’t need to untangle the draft yourself. I can help surface unclear reasoning, revise for flow, and ensure your message lands cleanly with decision-makers.

Start with a short estimate request, and I’ll recommend the right level of editing or summary support based on your goals and timeline. Ongoing or retainer support is also available if you prefer a steady partnership across projects.

Thanks for reading — here’s to clearer writing and stronger ideas.

~~ Susan